What is ATRIAL FIBRILLATION?

A rapid twitching of muscle fibrils in the chamber at the back of the heart (atrium) that receives blood from the veins draining into the heart. The atrium on the right side of the heart receives blood from the head, neck, torso and limbs, whilst the left atrium receives blood draining from the lungs.

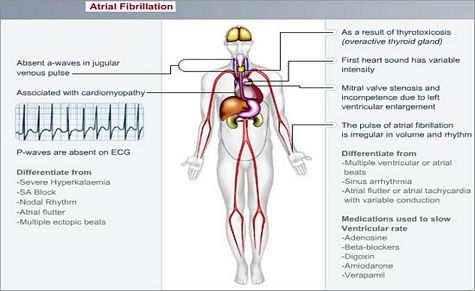

Atrial fibrillation (AF) may be chronic (present all the time) or only episodic (paroxysmal).

The atrium is responsible for ensuring adequate filling of the heart once it has emptied. When the atrium fibrillates, this function is significantly reduced.

Why does this happen and how may it affect the patient's health?

There are many causes, but the most common include

- High blood pressure

- An enlarged and weakened heart (cardiomyopathy)

- A narrow mitral valve (mitral stenosis); this valve opens to let blood drain from the left atrium into the left ventricle (main pump of the heart)

- Coronary artery disease

- Overactive thyroid gland (thyrotoxicosis)

- It may occur in the absence of heart disease or any of the other causes (lone AF); although underlying heart disease is common, more patients with paroxysmal AF have normal hearts than do patients with chronic AF

Treatment of these primary causes may abolish AF, but, with the exception of hyperthyroidism, this is rare.

Spontaneous reversion to normal rhythm may also occur.

What symptoms may the patient experience?

Atrial fibrillation usually causes symptoms. Patients may perceive the rapid irregular rhythm as disagreeable palpitations (an awareness of the heartbeat), or as chest discomfort.

The patient may also experience feelings of

- Weakness

- Fatigue

- Breathlessness

- Faintness

Those with paroxysmal AF often have more devastating symptoms, because of the sporadic changes in heart rate and regularity.

The blood in the atrium flows sluggishly and can therefore form clots in the atrium. These clots may dislodge at any time and cause, most commonly, a stroke. This occurs when an artery providing blood to the brain becomes occluded.

How is the diagnosis made and what special investigations are required?

A resting ECG will often reveal this arrhythmia.

For those with intermittent (paroxysmal) AF, a 24-hour ECG recording as an outpatient may be required if the resting ECG is normal.

What is the treatment?

Treat the underlying (causative) disorder e.g. an overactive thyroid gland.

Reduce the rate at which the heart beats. This is done with a variety of different drugs including Digoxin, a Beta-blocker, or a calcium antagonist (e.g. verapamil, diltiazem)

Try and restore the normal rhythm (sinus rhythm). In some, this may be achieved using medication (e.g. amiodarone), but DC cardioversion is a more optimal strategy. When the procedure is performed electively and if AF persists for >48 hours, prior thinning of the blood (anticoagulation) for at least 3 weeks is usually advised; this is done to reduce the risk of a clot dislodging from the heart and causing a stroke at the time of the DC cardioversion.

Prevent clot formation in the heart using anticoagulants (warfarin). Usually required for prolonged periods of time or even life-long.

Rarely, the heart rate remains very high despite medical therapy. As a last resort, the AV node, which allows electrical currents to move from the atrium into the ventricle, is destroyed. This can be done either surgically, or by means of a special catheter inserted via the groin into the heart. Following this, a permanent pacemaker has to be implanted to maintain an adequate heartbeat.

The chance of restoring sinus (normal) rhythm is less likely, the longer the AF is present (especially > 6 months), the larger the size of the atrium (back chamber of the heart), or the more severe the underlying cardiac disease.

If the cardiac disease remains unchanged, the relapse rate is high.

© 2003 Prometheus™ Healthcare (Pty) Ltd

|